Commissioning a Unique Piece to Celebrate Traditional Craftsmanship: Jochen Benzinger with Svend Andersen

In the watch industry masters of different trades work together. Jochen Benzinger is a specialist for decorative work on dials and movement parts, but he offers also watches bearing his name. I wanted one of his watches, though, he could not offer the additional complication required to fit the watch into my collecting theme. Svend Andersen had (for once) to slip into a supporting role, with the watch keeping the signature Benzinger look. Nevertheless, the contributions of the two masters of their trades turned out to be about equal, at least judging by what each of them has taken from my purse.

Above: Jochen Benzinger

THE TASK

I very much appreciate traditional craftsmanship in watches, with details only possible by handcraft. Furthermore, a likely silly tradition practised in the countryside in my childhood (saving expensive products from early wear, like a set of good clothes and shoes you only wear once a week to go to church) is in a way still ingrained in my mind. So, I am always reluctant to wear the Voutilainen GMT-6 when there is the slightest risk to bang the case at some door frames or scrape it along a wall in hectic daily life. Looking around for a suitable steel cased watch (showing traditional craftsmanship) for such occasions, I found the Subskription III model of Jochen Benzinger in a watch catalogue.

Above: Benzinger Subskription III; ETA 6498 manual wind movement, in-house redesign (hour and minute display moved off-centre); hand-guilloche dial; hand-skeletonized movement parts; flame-blued Breguet-style steel hands; flame-blued screws; stainless steel case made in Pforzheim, 42 mm diameter

Jochen Benzinger is much in demand by other watchmakers/manufacturers for his skeletonize, guilloche and engraving art practised in Pforzheim, Germany, for more than 30 years. You can have all of this handcraft art in infinite variations applied to the watches he manufactures in his own name since 2000. The ETA 6498 manual wind movement he uses for most models as basis comes with the seconds-indication at 6 o’clock. To pick up on the visuals of the Voutilainen GMT I so much enjoy, “only” a second zone time with a day/night-engraving has to be combined with the small seconds… A rough cut-and-paste job made a first enquiry possible.

For the Subskription III model Jochen Benzinger’s watchmaker is moving the hour and minute hands of the ETA movement off centre (what requires two additional gear wheels to be fitted to the movement). He declared forfeit when asked to add a 24-hour display turning anti-clockwise within the small seconds display area which, in addition, would have to be set independently of the main time with the help of a reference cities disk at the back of the movement. With this modification of the movement I wanted to get a time zone watch with a setting help.

Not giving up easily when I have something in mind, I asked Jochen Benzinger if he would agree to work with Svend Andersen, the latter being responsible for the movement work to get a second zone time display. No problem at all, because Jochen Benzinger is often creating custom watches in co-operation with other watchmakers than his own. And knowing that Svend Andersen has no “attitude” and is easy going within such collaborations, respecting the contributions of partners, I was convinced to get what I wanted.

Above: Svend Andersen

CO-AUTHORSHIPS

Jochen Benzinger is involved in different lines of watch manufacturing: Jaeger & Benzinger covers the entry level with less elaborate guilloche work and no skeletonizing of the movement; Benzinger watches are in the middle, while Grieb & Benzinger covers the upper range (employing precious metal and more elaborate cases as well as historic movements of Patek Philippe, A. Lange & Söhne and others). The bell signs at the entrance door to Jochen Benzinger’s atelier show all of these “entities”, even though there are different partnerships behind these brands. The skeletonizing as well as decoration work for these different watch lines are all done by Jochen Benzinger, while the watchmaking work is separated (for cleanliness) into a near-by atelier (Hermann Grieb runs a separate atelier in Schloss Dätzingen for the watches bearing his name).

Above: Jaeger & Benzinger Edition 1, ETA 6498-2

Above: Grieb & Benzinger models presented in January 2012 in Singapore, L to R: Blue Danube, split-seconds chronograph minute repeater, PP movement of 1890 for Tiffany; Blue Sensation, split-seconds regulator chronograph, PP movement of 1889 for Tiffany; Blue Whirlwind, Tourbillon minute repeater, PP RTO 27 PS movement.

Well-known brands come also to Jochen Benzinger. One of them was Chronoswiss to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the brand in 2008 with a special series of skeletonized watches called Zeitzeichen (“Signs of the Times Edition”). Chronoswiss was the first bigger brand allowing Jochen Benzinger to be named on the dial. Jochen Benzinger is very grateful to Gerd-Rüdiger Lang to give him this opportunity to become known to a wider audience.

Above: (LH) Chronoswiss Zeitzeichen Edition II; (RH) Chronoswiss Zeitzeichen Edition I; both based on the ETA/Unitas 6498-1 pocket watch calibre

My idea as a watch enthusiast to bring Jochen Benzinger together with an independent master watchmaker is not new: Peter Petzold of Define Watches in Australia wanted to combine the craft of Jochen Benzinger with watches of independent watchmakers he likes for very limited series.

Peter Petzold mentioned to have had no problem to convince Dirk Dornblüth: “Having worked in the same field for decades, both houses hold a deep respect for each other, so when asked by Define to join together to form a stunning new timepiece, both Dirk and Jochen jumped at the chance. Maintaining the Dornblüth DNA was a critical factor in the design, hence the typical D&S case structure and base calibre. In Dirk Dornblüth’s own words, Jochen Benzinger brings ‘soul to the piece by opening and embellishing the movement’.”

Above: 10-piece limited edition Dornblüth by Benzinger for Define Watches; Dornblüth & Sohn 99.1 in-house calibre (Photos: Define Watches)

When Peter Petzold conceived the idea of creating a Limited Edition Collection of 5-Minute-Repeaters that combine handmade horological perfection and aesthetic beauty, he wanted to commission Habring2 for the technical know-how and skill of owners Richard and Maria Habring, and Jochen Benzinger for the embellishments. He remembers: “Upon initial presentation of the idea, both parties were apprehensive, given the polar opposite of their approach to watch making and design. Richard Habring, co–developer of IWC’s patented Doppel-Chronograph, is an absolute purist with regards to the technical functionality of a watch. At Habring2 even an engraving on a crown is seen as an unnecessary complication on a mechanical timepiece. Habring2’s watches are strikingly understated; clean, clear lines and exceptional functionality underlie each timepiece produced by Maria, Richard and the small team at the manufactory in Austria. The prospect of an affiliation with a watch ennobler was both novel and challenging for a company that has built its reputation on understated design and technical functionality but both Richard and Maria rose to the occasion and realised that their core competence was exactly what would underpin the collection. So, despite the differences of execution, the philosophy of excellence unites the two and makes for a very exciting collection.”

Above: 5-piece limited edition Habring2 by Benzinger for Define Watches; Habring2 in-house manual calibre A 11B with Dubois-Depraz D90 Repeater module (Photos: Define Watches)

With all of this experience gained in external collaborations, I did not expect any hiccups with Jochen Benzinger working together with Svend Andersen. The project started with the part provided by Jochen Benzinger, because in this project he had not just the supporting role of decorating the parts delivered to him.

DECORATION DESIGN

Jochen Benzinger apprenticed as an engraver, what is not an exotic trade in his native Pforzheim. This town in southern Germany is (or was) the centre of the jewellery industry since the 17th century. Before the fashion jewellery took over (where an emblazoned brand name is the most important part), finger rings, ear rings, brooches etc. were produced with real handcraft. Skilled engravers, guillocheurs and skeletonizers were in demand to fill hundreds of jobs. Jochen Benzinger became a certified master engraver. Nevertheless, his real love for the (self-taught) art of guilloche developed early and he jumped at the opportunity to take over a guilloche (or engine turning) atelier when only 24.

He is least keen on hand sawing work to skeletonize his creations, so this part is now mostly done by a gold smith in his atelier; reducing the body of tiny parts with a hand saw is included in the formal training for this profession.

All three artisan crafts, having been developed to the highest levels for the famous Fabergé eggs (lately produced by Jochen Benzinger as a subcontractor), are involved in the creation of a Benzinger watch. You would think enthusiasts are indulging in the choices available; however, I had to learn from Jochen Benzinger that customers coming to see him with even a vague idea of what they would like are exceedingly rare. Therefore, he has always a selection of finished watches available for an “easy” choice. For me the involvement in the creation process is almost more interesting than the final possession of the watch, so I always like to find out about the possibilities offered.

Guilloche

It was a given for me not to go for an “open” dial, since an ETA 6498 movement does not provide a particularly grand view of motion work on the dial side to look at. I was rather keen to not only have a legible dial, but being able to enjoy the guilloche work created the traditional way (as Abraham-Louis Breguet did it) by Jochen Benzinger.

Comparing the visuals of the Subskription III with samples of Breguet’s work, it is easy to recognize where Jochen Benzinger got the inspiration for the design of his watch. He reveals himself as a fanboy of Breguet’s work when enthusiastically describing the decoration techniques employed since the end of the 18th century. Based on a Moser movement of the 1920s, Jochen Benzinger even honoured Breguet with a one-off pocket watch.

Above: Breguet & Fils, Regulateur à Tourbillon, No. 2555, 1824 (Photo: Antiquorum SA, Genève); Below: Benzinger, Subskription VI, Moser movement

I knew already Jochen Benzinger’s skills as a guillocheur from a Christiaan van der Klaauw Mondial CK-2 in my collection. When the Dutch master watchmaker still ran his atelier, part of the deal his customers got was an elaborate decoration of the ETA base movements by Jochen Benzinger. Four guilloche designs were proposed, which you could alter with your own details (or a family crest), though, you could have a completely unique design as well if your fantasy was good enough to provide ideas.

Above: ETA 2824-2 movements decorated by Jochen Benzinger for Christiaan van der Klaauw (Photos: Horloge Atelier Christiaan van der Klaauw)

Originally the guilloche (or engine-turning) was used since the late 15th century to engrave soft materials like wood and ivory. In Germany of the 15th until the 18th century the high aristocracy was trained in this craft, and ornamental wood turning became a “royal craft”.

Louis-Abraham Breguet is credited to have introduced this craft to watchmaking in about 1786. For him this artistic sculpting of the surface of dials and watch cases had not purely decorative purposes. The structured surface trapped also dust and dirt. This helped to keep the movement clean as best as possible before sealed cases could be made.

The decorative purpose reached a climax when Peter Carl Fabergé (as court jeweller of the Russian czar) started to apply translucent enamel over guilloche metal on his famous eggs from the 1800s onwards.

Above: Atelier of Jochen Benzinger in Pforzheim where all guilloche, skeletonizing and engraving work as well as flame blueing is done. Because these metal cutting processes leave dirt and dust, the watches are assembled in another atelier near-by. All galvanizing processes are subcontracted by Jochen Benzinger. (Copyright photo: Christian Bissener/Watch Collector Boutique; image used with permission of author)

The technique to apply a very precise, intricate and repetitive pattern by mechanical engraving to a material has never changed. The last rose engine lathes and straight line engines were produced in the 1930s. Everybody offering “hand-guilloche” decoration today has to find one of these antique cast machines and refurbish it. Jochen Benzinger had it a bit easier, because he could buy them locally when setting up the atelier. With the decline of the handcrafted jewellery the engines became surplus to requirements in many local factories.

Even though he is the only one doing guilloche work in the atelier, Jochen Benzinger has installed two rows of engine turning machines. This luxury allows him to set them up for specific work or even guilloche patterns and then just move from one place to the next instead of re-setting the engines.

When talking of “engines”, they are not regarded as machines in the industrial sense of the word but as tools. These “engines” are not powered. The craftsman has to use one hand to turn a crank which moves the workpiece (like the dial blank) and with the other hand he pushes the carriage bearing the graving tool (chisel) that engraves the material. The “engine” is thus just a tool that allows the craftsman to be precise and steady. Since the lines are all cut one after another, the dexterity and aesthetic sense of the craftsman are crucial. It is up to him (or her) to position the motif on the workpiece. The cranking speed and the pressure exerted on the graver as well as the precise positioning of the end of each cut are all decisive parameters for the quality of the end result. The human sensibility is thus required for each and every part decorated by guilloche craft.

Above: There are two types of engine turning machines; (LH) with the rose engine concentric circular or oval patterns can be made; (RH) the straight line engine is used to cut patterns either vertically or horizontally. (Illustrations: Deutsche Graveur-Zeitung und Stempel-Zeitung)

Above: To fix the dial on the tool, Jochen Benzinger uses engraver’s putty. Below: The putty is heated and the raw dial pressed on in a tool, a process that has to be repeated up to five times to ensure a flat positioning. Alternative fixing methods used in the industry are clamps or glue. (Copyright photos: Deutsches Uhrenportal/P. & M. Weigert; images used with permission of author)

I went for the traditional barleycorn pattern on the dial, which Jochen Benzinger likes too. It is not only the traditional guilloche pattern used by Breguet, but is in my opinion also appropriate to fit with the quite boxy case of the watch. Interest is added with the optical illusion of “rays” running in a sweeping curve towards the centre of the dial. This illusion is created by sticking to the same number of “waves” (72) in the lines engraved around the dial (from the outside to the innermost part) and by keeping the same distance between these lines – something that seems almost impossible when using a CNC engraving.

Looking at the chisel engraving the dial, I am always amazed what delicate patterns can be done with such a coarse tool. The thickness of the Subskription III dial varies from 0.3 to 1.2 mm due to turnouts on the back. The engraving can therefore only have a depth of 0.25 mm, and the dial has to be precisely fixed in a flat form for constant depth of the engravings. The depth stop (touche) fitted parallel to the cutter that runs on the not yet engraved part of the dial is not saving the work piece from ruin by clumsy treatment; it is easily possible to apply too much pressure to the slide and cut through the dial, or distort it by pressing the stop into the material.

The guillocheur needs in addition a lot of experience for all the choices to be made: fit the correct rosettes for the intended engraving pattern; choose the right “touche” for rosette and cutting tool; pre-adjust the cutting depth; and adjust the different centres used on the dial. Full concentration is needed to remember and adhere to the sequence of the required settings (changes for every line done manually by ratchet) of the chisel carriage as well as the rosette cylinder for line form changes. The slightest slip of concentration produces a dial for the scrap heap.

Above: Jochen Benzinger does not work with a microscope as often seen (e.g. at Kari Voutilainen’s guilloche atelier). Since engravers learn the trade without these extreme sighting helps, they would irritate him.

It takes about nine hours to just engrave the dial with a fairly simple pattern as used for my watch. This raises the question, if someone other than an engraver can recognise a dial actually decorated laboriously by hand? Superficially, a dial with a stamped guilloche pattern or one created with a CNC mill looks just the same for a layman. Or does it?

Today’s industrial techniques allow ever more to visually replicate hand craftwork. When dial manufacturers are sometimes asked in interviews, how you can recognize real hand-guilloche work, they often struggle to name decisive criteria. Stamped guilloche patterns are described as too regular and without the play of light the real engravings offer. To differentiate hand-guilloche from CNC milled engraving lines, the former should show according to these specialists: a) gradual thinning of each line at the end of a stroke; b) a cut with distinct flat sides to each side of a sharp bottom edge; c) tiny striations along the flanks of the engraved “valleys” created by the chisel (a rotating cutter of a CNC mill would produce perpendicular markings). Without a microscope or at least a highly magnifying loupe it seems impossible to me to check on these “scientific” criteria as a mere amateur. I believe it is more successful to look for tiny irregularities which are likely to be found when I consider all the parameters of the handcraft influencing the final result. And usually these can be found. For those who appreciate handwork, such tiny “faults” provide the sought-after charm to a dial (or other engraved part of the watch) as well as uniqueness. Armchair “experts” judging watches based on macro photos viewed on the screen frustrate Jochen Benzinger when they then write about shoddy workmanship on certain blogs. To treat metal with a chisel or burin (literally tearing metal out of the piece worked on) creates inevitably a coarser surface compared to inward angles and bevels polished with wood sticks to perfection. While the latter decoration of parts can be seen all the time in the press, the method practised by Jochen Benzinger is hardly ever presented. Without explanation it might therefore also be difficult for a casual viewer to understand a process induced surface appearance.

Frosting

For the Subskription III model Jochen Benzinger uses a two-part dial, with the upper part cut by wire erosion and glued on top of the main dial when both parts are fully finished. Both dials are made of 925 Sterling silver that includes 7.5% other metals, particularly copper to harden the alloy. Jochen Benzinger made this choice to create dials the way Breguet did, while elsewhere solid gold is mostly preferred (which has then to be silvered by galvanic process).

Above: The MB&F LM 101 Frost model shows what is usually meant by “frosting” in industry speak: A mechanical surface treatment of metal by wire brush (or bead blasting). (Photos: MB&F)

“Frosting” can mean different things. MB&F elaborates in the press release for the LM 101 Frost model in what a dangerous way Breguet and others produced the frosting (“finition grenée” in French) with “powerful acids” and that alternatives had to be found, like the careful treatment of the surface with a wire brush, as MB&F does it to decorate plates and bridges. Yet, these are different processes.

The Breguet frosting of the dial is not a mechanical surface treatment (compressing) with wire brushes or even bead blasting (what produces the grained surface of movement parts as it has become so popular), but rather using heat and chemicals to get this silvery-white surface with a subdued sheen. In German this method is called “Weisssieden” (blanching). Breguet used this method to seal the surface and avoid oxidation of the silver. The tarnishing of the silver is the result of the oxidation of the non-silver parts in the alloy, particularly the copper. Heating the dial on the flame, the non-silver parts oxidise and colour the piece completely black. This black deposit on the surface is washed off with diluted sulfuric acid. The process has to be repeated six to eight times by Jochen Benzinger until the whole surface is only covered by pure silver visible as the white-silvery deposit.

The lower dial with the barleycorn guilloche is left in this state. On the other hand, the upper dial is carefully ground to show up the area to be printed with numerals in typical silver without the whitish frosting; the latter remains only visible at the bottom of the Breguet thread guilloche pattern on the upper dial. Jochen Benzinger paints afterwards the dial with a very thin clear lacquer coat. The dial requires this protection after the previous treatment not to avoid a tarnishing, but to save it from imperfect painting of the numerals. Listening to him I got the impression that the printing quite often requires more than one attempt for the desired result. The protective lacquer allows wiping off the unsuccessful printing. Leaving the dial as Breguet would have it, the printer would ruin a complete dial in these cases. With all the time invested beforehand, Jochen Benzinger does not want to take such risks.

To match the traditional crafts, steel hands and screws are flame blued. To go with the blue, I have chosen a rhodium plating of the brass movement parts (with a few exceptions in 5N gold plating, to add a bit visual interest to additions made by Svend Andersen).

Skeletonizing

With the traditional skeletonizing all non-essential metal of the bridges, plate, wheel train and further mechanical parts are trimmed away to leave only the absolute minimum of the movement required for its function. The surplus material is cut away with a goldsmith’s saw. This original technique retained the exterior contours of plates and bridges; material was cut from the inside of the parts. What then remained was finely decorated with hand-bevelling and hand-engraving.

It is believed, the original idea of this embellishment was to draw attention to the gear work of the watch and generate interest for these mechanical wonders. Many skeleton clocks were made during the final years of the 18th century. Masters of the craft got soon the ambition to create the most filigree skeletons possible, putting the skeletonizing work itself into the centre of attention, particularly when this art spread to wristwatches. One leading master is Armin Strom who even managed to get an entry into the Guinness Book of Records for the smallest hand-skeletonised watch.

(Photo: Armin Strom AG)

Another Swiss specialist of this craft is Kurt Schaffo, whose son Christophe continues the tradition (e.g. with work for Moritz Grossmann Glashütte).

Above: (LH) Kurt Schaffo, model Charme; (RH) Christophe Schaffo, model Tourbillon I

This traditional skeletonizing work would likely (at least today) be seen as better suited for female than male wrists. The skeletonizing art is still alive, though, no longer as an ornate decoration. It brought a design language associated with race cars (and particularly their suspension systems) to watches. A pioneer was Richard Mille in 2000. Today, the most extreme samples are offered by Roger Dubuis with the metal structure replaced by carbon skeletons.

Above: Roger Dubuis Excalibur Automatic Skeleton (Photos: Manufacture Roger Dubuis)

These modern skeletonised movements are all designed this way and not created as afterthoughts. A variant of the same idea are the open-worked movements. Sernier/Papi (High End horological finishing and decoration, 2008) use “Openworking” and “Skeletonzing” as synonyms. This is not generally accepted. While Armin Strom labels its open-worked collection Skeleton Pure, CEO Claude Greisler stresses in interviews that not transparency of the movement is the goal, but enhancing the three-dimensionality to offer the viewer the possibility to better appreciate the layered construction of the movement.

Below: (LH) Armin Strom Skeleton Pure Water; Calibre ARM09-S (Photos: Armin Strom AG); (RH) Audemars Piguet Double Balance Wheel Openworked; Calibre 3132 (Photos: Audemars Piguet)

Jochen Benzinger does not keep the exterior contours of the ETA’s plates and bridges intact. He rather decides what material is required working from the given fixing points and bearing positions of the movement on hand. He mentioned that for him the skeletonizing has furthermore the purpose to disguise a bit the ETA movement to casual viewers, because this can be an issue with the watches at the higher end of his price range. He considered to use a new manual wind movement from an independent Swiss manufacturer. With the small quantities he needs, it would increase the base movement costs more than ten times. So for the time he is carrying on with the well proven pocket watch movement Unitas/ETA 6498-1. Its size ensures a well-filled case, and the skeletonizing style developed by Jochen Benzinger leeds to a “beefier” look, closer to the modern visuals described than the traditional filigree work.

The alternative – picking up on the current trend of skeletonzied or open-worked movements in a more modern style –, is used by bigger manufacturers when they employ the ETA 6497/6498 movement. First of all the Swatch Group itself with a Tissot model. The design/technique applied here is perhaps not universally judged as an especially successful job. On the other hand, it cannot be complained too loudly with a watch costing less than $ 1’800.00.

The small brand Aerowatch manages to offer an ETA 6498 movement quite successfully (in my view) cut-up by CNC for the technical look without a purpose designed movement.

Above: (LH) Tissot T-Complication Squelette Mechanical; ETA 6497 (Photo: Tissot SA); (RH) Aerowatch Renaissance Skeleton; ETA 6498 (Photo: Aerowatch AG)

At Jochen Benzinger to cutting is all done by handwork, using a goldsmith‘ saw. He has developed his own style of skeletonizing, finding a middle line between the traditional filigree work and the designed technical look of modern watches.

His skeletonzing is offered in three basic variants: The “floral” design requires a shaping of the skeleton by hand engraving (and he recommends this embellishment only for women’s watches); the “Kringel” (curl, ring-shaped) design and the square cut skeletons are decorated on the rose engine.

Above: (LH) What Jochen Benzinger calls the “floral” design of skeletonizing has to be done by hand engraving; (RH) the “Kringel” design is created on the rose engine. Below: With a “beefier” skeleton the guilloche decoration can be cut deeper to make it better visible.

For me only the guilloche decoration was viable, because I thought it complimentary to the shape of the case as well as matching the decoration chosen for the dial. Furthermore, this style is unique to Jochen Benzinger, nobody else offering skeletons decorated with the rose engine.

Jochen Benzinger designs the skeleton lacework usually from scratch for every watch (with the exception of watches he produces for his stock). I did not know this and only found out later on when seeing the drawing he had made for my watch. Without a clue where “meat” has to be kept, I could not contribute suggestions in any case. When a guilloche decoration has been specified, the “bones” of the skeleton have to be part of a circle to work it on the rose engine, i.e. in the same technique as for the dial decoration. On my watch he has laid down three principal circles, with balance, spring house and minute wheel providing the respective centres.

Jewels, feet and screws of the movement have to be retained in their original positions in a stable way. The rest of the plates, bridges and cocks are at disposal to give the movement a new appearance. Jochen Benzinger’s method to design the skeleton removes the typical contours of the movement parts.

Above: The guilloche decoration is applied on the the original plates and bridges. Bridges and plates have to be fixed on a tool to bring the surfaces onto the same level for this work. Below: The surplus material is afterwards carefully cut away, using the applied decorations as guidelines for the cuts.

While the brass parts of the movement were rhodium plated and the steel gear wheels of the ETA blued (galvanic process), the gear wheel with the 24-hour numerals printed on was plated in 5N (rosé) gold to highlight its display function.

Above: The finished, rhodium plated guilloche work on the movement of the Benzinger-Andersen watch.

More elaborate designs

Jochen Benzinger offers much more complicated decorations with hand engravings. Such commissions require detailed discussions with the customer as well as preliminary draft illustrations. Notes and illustrations are done by Jochen Benzinger in his distinctive free hand writing and drawing, with no computer in sight.

This time I did not want to go into such elaborate visual treats, but rather use a restrained design to not distract from decorations applied by rose engine.

(Copyright photo: Christian Bissener/”Watch Collector” Boutique; image used with permission of author)

Bezel

In addition to the polished bezel with flat surfaces, a fluted version is offered as an alternative. I did not like the standard, polished version, and neither the applied flutes. The latter are in my eyes a trade mark feature of Hanhart as well as Chronoswiss watches (and look therefore derivative on a Benzinger). In addition, rounded flutes felt not right in combination with all the geometric shapes on the rest of the watch.

What I like I found on the Grieb & Benzinger watches: The “squared” bezel with a guilloche decoration. But stainless steel is too hard for applying a guilloche pattern on the rose engine. I went therefore for an 18k white gold bezel. Later I learnt brass (to be rhodium plated) could have been used, though, Jochen Benzinger prefers the gold, since fine lines are easier to get with it.

Above: Fluted stainless steel bezel (LH); guilloche bezel in white gold usually only offered with Grieb & Benzinger watches (RH).

Engraving and Printing

In addition to the guilloche work, further engravings are part of a Benzinger watch. The screw-in case back sports a lot of wording (applied with a pantograph since it is not possible to engrave stainless steel with a burin) if the customer is not specifying his own design. All this redundant wording on watches is a pet peeve of me. So the text was reduced to the master’s name, and his place (Pforzheim) added for the sake of symmetry. “Unique Piece” or “1/1” is the only additional placard I quite enjoy when appropriate.

I would have liked all the marking dots and numerals as well as the text on the dial not printed, but engraved, even if a laser had to be used. While Jochen Benzinger cited excessive costs first to deter me, he had in the end to reveal the technical reason for trying the utmost to “sell” a pad printing instead: For the traditional Breguet frosting of the upper dial it has to be heated several times in between grinding and polishing to get the “naked” silver base to apply the numerals and lettering on. If this surface has been partially weakened or thinned by an engraving, small distortions are almost unavoidable with this process. In the end a slightly wavy surface would be the result with almost certainty. Since Jochen Benzinger has no way to control this, he does not want to experiment with engravings on the upper dial. OK, then it is accepted…

On the other hand I was adamant to have the back cover properly aligned (knowing how difficult it is with a screw-in back), with the lettering and the recesses to insert the opening tool in an appropriate position relating to lugs and main crown. On press photos the watches are presented like this. Jochen Benzinger declared it pure pot luck to get it this way because it seems not a criteria when milling and threading the case. I had no such luck with the case of my watch, so the problem was moved on to Svend Andersen. With some fine tuning and juggling with different seals he managed to get an acceptable alignment.

For the day/night-disk on the dial nothing else than engravings were accepted. This disk (to be produced by Svend Andersen) required a “sunny” and a dark part. Knowing that I prefer to use the natural colour of materials to painting, Svend Andersen suggested a two part disk: The day represented by red gold and the night by blue gold, a speciality of Andersen Geneve. “Blue gold” is a special alloy (of pure yellow gold and iron) introduced by Ludwig Muller of Geneva in jewellery many years ago. Svend Andersen has taken over this material for watchmaking. For the secret process with flame heating he has still to employ Ludwig Muller’s son Martin. By heating the material, the iron molecules come to the surface and the oxidation colours the surface blue. The process leaves a layer that hardens and seals the surface of the piece. I thought this complements the frosting technique employed by Jochen Benzinger for the dial.

Since I don’t care where craftwork is done when quality is produced, the legend “Hergestellt in Deutschland” (“Made in Germany”) at the bottom of the upper dial had to disappear. Instead, the space was offered Svend Andersen to indicate his co-authorship. This was not without problems, with several attempts necessary to handle the different letter count of the two words. I am still not quite happy with the spaced out “Geneve”, yet better alternatives were not found; I accepted it in the end, because Svend Andersen uses this different letter spacing also on his letterhead. And yes, in real size you don’t see all these details on the watch driving you crazy when looking at them magnified several times…

The two part disk went to Jochen Benzinger for a “sun ray” guilloche decoration, respectively a hand engraving with symbols of the night (moon face and stars). I was sent first a drawing for approval.

LH: Red gold part with a sun ray pattern guilloche; Centre: Hand-engraving of “blue” gold part before the heating process brought out the blue colour; RH: Finished disks fitted to the base gear wheel.

CHANGE OF TASK: Worldtimer with 24 Hour Display instead of Time Zone Watch

My original idea was to have a time zone watch with a setting help by reference cities at the back of the movement. I prefer this arrangement to a proper worldtimer, because you can avoid the visual domination of the dial by the device to permanently show the time in at least 24 zones (either a central disk with reference cities as Tissot/ETA offers it, or the peripheral 24-hour and reference cities disks of the Cottier-system used by Patek Philippe and many others). Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced in 1990 with the Geographique model the quick setting of a second zone time displayed on the dial. A disk with reference cities was connected to the movement, sparing the owner to know or remember time differences in between locations when setting an additional time display.

Above: The initial task given to Svend Andersen was to take the idea of Jaeger-LeCoultre for a second zone time set with the help of a reference cities disk, using the more decorative sample of Kari Voutilainen for the second time display by disk instead of hands.

I wanted to use the same construction principle, but moving the reference cities disk to the back for a “cleaner” dial. With the Benzinger watch such a solution was unfortunately not possible. The second time display on a 24-hour disk turning in the opening for the small seconds at 6 o’clock could be added with no problem. Unfortunately space problems hindered a time setting independently of the main time display: In addition to finding space for the mechanism of a pusher or an additional crown, more importantly, room for another height level within the movement would have to be created to accommodate a further wheel set. Svend Andersen could have happily modified the movement for this function, if another case with about the height of the bezel added is supplied. The further height added to the already substantial case was not desirable for me, and the costs for a one-off case could not make sense with this project.

So, what to do when I am already fixed on an idea as well as specific visuals of the dial? Svend Andersen suggested adhering to the idea of an additional 24-hour display on the dial, without a convenient exterior device to make it separately adjustable. A watchmaker could still set it for another zone time, or it could be used as an am/pm marker to support the main time display. To compensate the limited functionality of such a 24-hour display on the dial, a world time display would be installed on the back side of the movement.

Above: (LH) Jochen Benzinger delivered a fully functioning, not yet decorated watch to Svend Andersen. When the photo was taken, the additional parts produced in Geneva (like second crown and base disk for 24-hour display) had already been fitted in their raw state. Jochen Benzinger needed the watch with the parts modified/added by Svend Andersen fitted to design the pattern for the skeletonizing of the movement. Therefore, the watch went back in this state to Jochen Benzinger for its decoration. (RH) The 24-hour display is a three part construction: a brass gear wheel at the bottom, a brass disk with three threaded holes to be screwed to the gear wheel, and the – here not yet fitted – 2-part gold disk (day/night) glued on top of the brass disk.

24-hour Display (Front)

Above: (LH) At Andersen Genève the space required for the additional gear wheels is created with a Burin fixe, an old hand operated watchmaker’s lathe. For the 24-hour display not only a tube around the seconds hand shaft had to be fitted as pivot, but also a recess created in the plate for the additional gear wheel. (RH) The denuded under dial view of the ETA movement shows the – red circled – position of the hole to pass the pivot to power the 24-hour display on the back side. The direction of rotation of the gear wheels is also checked again before drilling the plate.

Above: A piece cut from a sheet of brass is the basis, e.g., for the gear wheel of the 24-hour display. After cutting the teeth, a recess is milled into the 24-hour gear wheel to create space for the day/night-disk, provisionally fitted here in its raw state. An intermediate gear wheel for the 24-hour display is also required.

Below: The two grey steel gear wheels in the centre show the movement modification by Jochen Benzinger to move hour and minute hands off centre; the gear train in brass was manufactured in the atelier of Andersen Genève by Gaël Petermann to get the 24-hour display on the dial, connected to the main time display. The gear wheel calculations were checked in a trial fitting.

Above: (LH) The under dial gear train finished… (RH) … with corresponding recesses milled into the backside of the dial to fit all into a standard Benzinger case.

Above: When all worked in the raw state, some “decorations” were added to plates, though, with the closed dial they will only be visible to watchmakers taking the watch apart again.

Below: The white gold bezel with its “softer” colour compared to stainless steel eases the transition to the silver dial on the finished watch.

World Time Display (Back)

Below: A pivot guided through the movement transmits the drive taken from the hour wheel to the back of the movement to drive the 24-hour display.

Above: A gear wheel at the centre of the back of the movement was to become the 24-hour “disk” for the world time display.

Below: Gaël Petermann prepares the centre of the 24-hour display wheel at the back of the movement to fit a pivot.

Above: To give a better view of the decorated skeleton, the gear wheels for the 24-hour display at the back were crossed out to form “spokes”. On the crown and ratchet wheels in steel, Jochen Benzinger had to do this job later on.

Above: (LH) A bezel for the sapphire disk was turned in the atelier of Svend Andersen. (RH) A very thin brass ring with fine teeth was manufactured and glued at the underside of the sapphire disk; it allows turning and positioning the disk in the desired position with the help of an additional crown.

Below: An additional crown with a rubber disk makes it possible to align the reference cities printed on the sapphire disk with the 24-hour display indicated on the central gear wheel/disk.

For Svend Andersen the solutions chosen have to be practical. He prefers sans-serif lettering and numerals, whenever space allows, even in bold type. This helps with legibility, according to him. Even though I like functionality, I don’t put ease of reading off the watch at the top of the priorities, especially when I feel the type does not quite fit the overall design. While I accept the lettering preferred by Svend Andersen on his own watches as some kind of “trademark”, in this case I wanted to have the say.

Above: Not being a designer or even a skilled illustrator, I have always to look for existing samples to explain what I prefer. An Orient world time watch gave me a sample of serif type lettering I could use for another cut-and-paste-creation to show what I tried to describe.

Svend Andersen asked his graphic designer for proposals. One (below, LH) picked up the typography used by Jochen Benzinger on the dial. There was just another “practical” detail I thought did not enhance the visual impression: The dots alternating with numerals had to be centred since I felt to be able to find the relevant marking line without the dot being so close to it (below, centre).

Above: (RH) Svend Andersen gave not yet up and presented a proposal for a practical radial arrangement of the reference cities. I ignored this because I wanted the references for the time zones at the periphery of the sapphire glass to not obstruct the view onto the skeleton and guilloche work of Jochen Benzinger.

Above: Making a “photo montage” with an acetate template held over a photo, I was convinced this solution could work, not the least because enough of the movement decoration stayed visible.

Above: When provisionally fitting the screw-in back it was noted that there was not enough room left for the internal sapphire disk with the reference cities to clear the swan-neck properly. I had ordered this addition from Jochen Benzinger to dress-up the movement a bit. What Svend Andersen thinks about it, I quickly learnt: For him it is a useless “crutch” on the ETA movement with its limited setting range; a competent watchmaker should be able to adjust the 2-part regulator without the addition of such a “micrometer”. So he was glad that the swan-neck had to be removed. And Jochen Benzinger was asked to produce a new balance cock without holes for a swan-neck fixing…

BREAKDOWN OF COMMUNICATION: For once an Advantage

In previous projects I had it too easy and got rather negligent to confirm myself in a clear way what features of the watch have been laid down. With unique pieces involving several craftsmen and “criss-crossing” communication paths, the customer should really assume the role of a foreman, with a working paper binding for everyone involved and being updated regularly. Though, I did it not, believing, e.g., it to be clear from the beginning that the day/night-disk has to be combined with a 24-hour display (as illustrated in proposals), otherwise it would only be a decoration without function. I only realised that in Geneva it was not seen this way when the disk was already finished. When I ordered a new one incorporating the hour display, Svend Andersen asked if the diameter of the day/night-engraving would then not be too small to show all the work that goes into it (the diameter of the hole in the dial was given).

Above: (LH) The day/night-disk without time indications and … (RH) … instructions for rectification I gave.

Fortunately he could offer an alternative: Why not fit a sapphire glass with the hour markings on top of the disk, a solution that would match the one chosen for the world time display on the back side? First I was sceptical but felt there is not more to lose than a sapphire glass if I don’t like it.

Proposals how to mark the sapphire glass followed. I wanted to avoid dots competing with those on the dial, and all markings moved to the edge to really leave the best possible view onto the engravings on the disk.

Seeing the final result, I am glad we had this misunderstanding. The solution fits – in my view – the rest of the watch much better than what I first wanted. With hindsight I am even a bit ashamed how unimaginative my idea was, much too fixed on the design Kari Voutilainen uses on the GMT model.

Nevertheless, I vowed that I will really keep an illustrated spreadsheet with all the discussed details with future projects.

METHODS TO CREATE A UNIQUE PIECE

If you want a Unique Piece designed, constructed and documented to the standard of the industry, you can expect to run up hefty development costs before production of parts starts, with around CHF 15’000.00 for the reconstruction of an existing, not too complicated movement, and about CHF 10’000.00 each for the integration of a GMT or world time function (based on existing modules). And this from a supplier to the watch industry, with a flexible organisation experienced in conceiving movements/complications as well as prototyping them.

Such costs were out of question in this case, because it would have undermined the concept of a not too expensive “every-day-watch”. There was just no development budget available here.

The final product was thus also the development hack and the prototype. This makes it almost unavoidable that parts already finished by third parties (like glass disks with their delicate printing on it) get slightly worn by the repeated handling and testing. Striving for perfection in watches, it got sometimes frustrating for me when macro photos then show here and there a marker or letter that has lost part of its paint body. If you struggle to accept this kind of imperfections (as I do) only visible under a loupe, the question arises what parts have to be redone to bring such details up to series build quality. At the moment I have not yet quite found peace of mind. I hope the imminent final detailing round will bring the project to its definitive end.

Even though Svend Andersen had a stickler for details with me as customer, he had to choose very pragmatic methods in a project where keeping costs in check had a high priority. Accordingly there is also only very sparse “documentation” to be found in the folder for “Reference 623” (in addition to the illustrations and clichés of the graphic designer for the printing), namely a calculation of the required additional gearing.

The initial decisions were made by looking at the roughly assembled watch supplied by Jochen Benzinger: Where could the additional gear wheels fit, what sizes are required for them and where do you find space to transmit the power for a 24-hour disk through the movement to its back side? The next move was to walk to the back room of the atelier and grab brass and stainless steel rods stored there with other raw materials. Now go to the lathe and start production of the required gear wheels and pinions, with the gears cut on another machine.

This is, of course, over simplified. But there was no CAD involved and nobody drew any plans to task a third party with the construction of what was needed. I believe there is a place for such a much reduced process when you only want a relatively simple movement modification. For this to work, I required someone with the experience and willingness of Svend Andersen and the young, skilled watchmaker Gaël Petermann to take on a task like this with confidence. As customer I know all is OK when I am handed over a watch running well and with everything smoothly operating. And with someone like Svend Andersen I have the assurance to come back anytime when something should turn out not to be the optimal solution after all. So far this was not necessary (bar some minute detailing still going on). I am grateful that all involved had such a relaxed attitude to work together without problems, and to accommodate my foibles and wishes as well.

So, what is the moral of this story? If you think (as watch enthusiast) Max Büsser and Steven Holtzman have a dream job conceiving new watches for MB&F respectively Maîtres du Temps and working together with master watchmakers, you could easily organise a work trial for yourself. Should you not seek the challenge (and costs) of an elaborate new movement, unique pieces with functions added are available at bearable prices when masters used to create “freehand” are hired. Personally, I enjoy decorative craftsman art on watches as much as a complicated movement. This makes it even easier to get satisfaction from being involved in the creation of a new watch as an amateur. You will have to make your ideas and wishes understandable as well as coordinate the work of masters, just the way those two gentlemen have to worry about. For me the educational process provided is exciting with such projects, because I learn in detail about manufacturing techniques and material properties I would not appreciate sufficiently by just looking at the finished product. To get a bit more involved with artisanal crafts than just marvelling at the final results was truly fulfilling, even if my own hands could not contribute.

FURTHER INFORMATION

In 2007 Ron Weis presented his Benzinger Unique Piece and added an article originally published in the NAWCC Bulletin as well as an interview with Jochen Benzinger first published in International Wristwatch. Since the production methods of Jochen Benzinger have not changed since, this post is still relevant http://bit.ly/2BFcWqN

Jochen Benzinger produced short films to better illustrate his work:

Guilloche-engraving https://youtu.be/XDF-Y5QItMk

Skeletonizing https://youtu.be/GSgQ7hV9ULc

Engraving https://youtu.be/c2TuYU1-nA4

Björn

(Photos: Jochen Benzinger, Andersen Geneve, Gaël Petermann, Deutsches Uhrenportal/P. & M. Weigert, Peter Petzold/Define Watches, Christian Bissener/Watch Collector Boutique, Jürg Meier)

Next Article

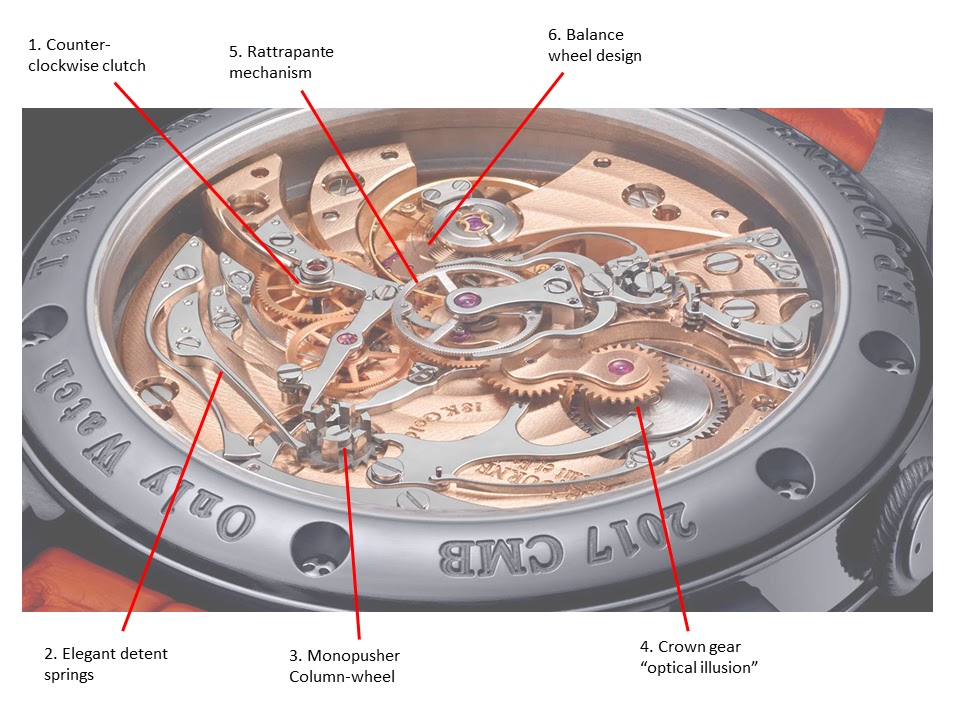

F.P. Journe Monopusher Split Seconds Chronograph – a Movement Analysis

© 2017 - WatchProZine